-40%

Vivien Leigh w/ Producer David O Selznick Gone with the Wind Set Photograph 1939

$ 2.61

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

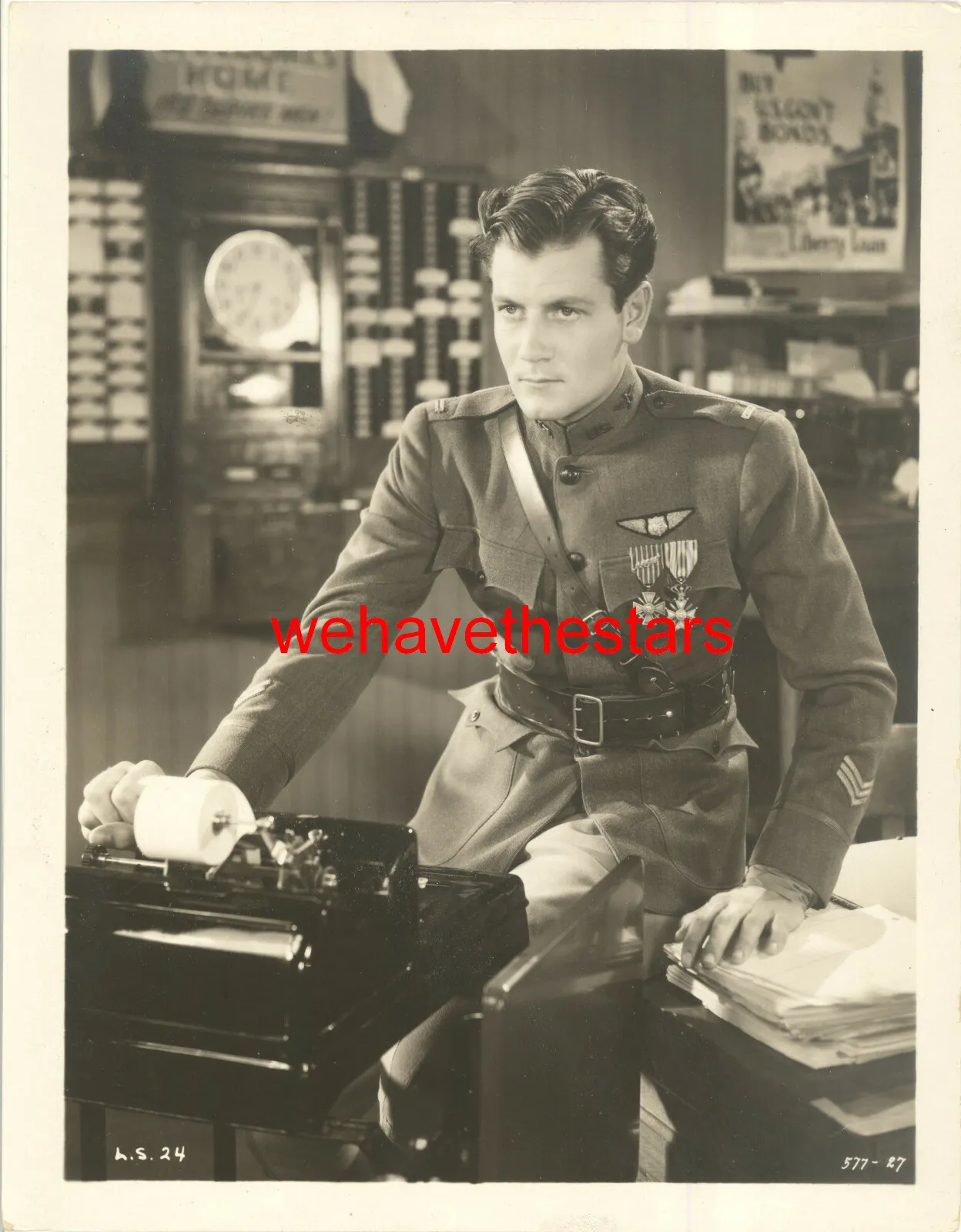

ITEM: This is a vintage and original Selznick International Pictures production still photograph from the Golden Age of Hollywood blockbuster "Gone with the Wind" (1939). This candid photograph captures the film's producer, David O. Selznick, chatting with the film's star Vivien Leigh. Just a wonderful behind-the-scenes memento from one of Hollywood's biggest films. The press snipe on verso reads:SCARLETT O'HARA was the most sought after role in Hollywood as soon as David Selznick announced plans for "Gone With the Wind." But he didn't pick the actress until after filming had started. And to play the classic southern belle he finally chose an English actress--Vivien Leigh.

The movie, which earned a record 13 Academy Award nominations and won 10 Oscars (eight in competition and two honorary awards), was selected to be preserved by the National Film Registry in 1989 and has placed in the American Film Institute's list of top American films every year since the inception of the list in 1998. "Gone With the Wind" was the longest, most expensive and successful Hollywood sound film up to its time. Its Oscars included one for Best Picture in competition with such other classics of Hollywood's "Golden Year" of 1939 as "The Wizard of Oz", "Stagecoach", "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" and "Goodbye, Mr. Chips". Made for around million, GWTW still holds the box-office record for domestic gross (adjusted for inflation) at .6 billion.

Photograph measures 8" x 10" on a glossy single weight paper stock. Studio paper caption on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Vivien Leigh:

A lovely, petite, fragile stage-trained player whose delicate beauty first graced the screen in 1935, Leigh was born to a British military family stationed in India. Despite her heritage, she remains best-known for her two most successful screen roles as American Southern belles.

After a childhood traveling Europe, an apprenticeship at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and a brief marriage, Leigh began her career in 1935 with several small stage and screen roles. After making a hit onstage in "The Masque of Virtue" (1935), she was signed by Alexander Korda and appeared as a pretty ingenue in such films as "Fire Over England" (1937), opposite Laurence Olivier, and "Storm in a Teacup" (also 1937), with Rex Harrison. Korda loaned her to MGM for "A Yank at Oxford" (1938), which did more for Robert Taylor than Leigh. That same year, she displayed her screen charisma and charm as a Cockney petty thief who is befriended by street performer Charles Laughton and romanced by songwriter Rex Harrison in the frothy "Sidewalks of London/Saint Martin's Lane." While making her mark in features, Leigh continued to polish her talents onstage, notably as Ophelia to Olivier's "Hamlet" in 1937.

By this time, Leigh and Olivier were romantically involved. When he went to the US in late 1938 to make "Wuthering Heights," Leigh followed and won the much-coveted role of Scarlett O'Hara in "Gone With the Wind" (1939). Her Scarlett was a headstrong, willful and colorful portrayal. Despite much flack about a relatively unknown Brit taking the role of the quintessential Southern belle, Leigh was triumphant, won an Oscar and became a bigger star than Olivier (whom she married in 1940).

Leigh failed to immediately follow up on her tremendous promise. She starred onstage with Olivier in "Romeo and Juliet" (1940) and made two films. In the fine remake of "Waterloo Bridge" (1940), Leigh's beauty heightened her portrayal of a ballerina in love with an upper-class soldier (Robert Taylor). Through a series of plot machinations, she is reduced to prostitution and has a bittersweet reunion with Taylor, whom she thought was killed during the war. The role was the first of many in which her character suffered mental collapse--ironically mirroring her own bouts with mental illness. She again was a woman of questionable virtue in the biopic of an historical tart in "That Hamilton Woman" (1941, opposite Olivier). Her subsequent career was slowed to fits and starts by the tuberculosis which eventually killed her, and by her own emotional instability.

For the rest of her career, Leigh alternated between the stage and screen, giving electrifying, emotional performances in both mediums. She appeared in six films after her initial bout with Hollywood, first in the British productions "Caesar and Cleopatra" (1946), opposite Claude Rains, and as "Anna Karenina" (1948). Her next huge hit was recreating her stage role as the fragile, emotionally unstable Blanche Du Bois in Elia Kazan's film of Tennessee Williams' "A Streetcar Named Desire" (1951). Her performance as the outsider is enhanced by playing off her Method-trained co-stars, notably Marlon Brando's stunning Stanley, Kim Hunter's torn Stella and Karl Malden's gentle Mitch. Leigh earned a second Best Actress Oscar playing this damaged woman trailing the tattered threads of her sanity behind her, a role some felt was eerily close to Leigh's own personality at times. Her last films consisted of stellar performances as emotionally unstable women in less than stellar films: "The Deep Blue Sea" (1955), as a frustrated, suicidal wife; "The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone" (1961), based on a Tennessee Williams' story, as an elegant, middle-aged actress who is ample bait for Warren Beatty's gigolo; and Stanley Kramer's all-star "Ship of Fools" (1966), as an embittered, flirtatious divorcee.

Leigh was, perhaps, happier onstage. She and Olivier toured with the Old Vic company in the late 1940s and early 50s, in such plays as "The School for Scandal," "Anthony and Cleopatra," "Caesar and Cleopatra," "Richard III" and "Antigone." She was directed by Olivier in "The Skin of Our Teeth" (1945) and "The Sleeping Prince" (1954) and scored successes with "Duel of Angels" (1958) and "Look After Lulu" (1959), directed by Noel Coward. In 1963, she made her American musical stage debut in "Tovarich," winning a Tony Award. But health problems began to interfere with her ability to sustain a long run and she frequently missed performances. Her last stage appearance was in "Ivanov" in 1966.

Leigh's private life was as stormy as any of her roles. After twenty tempestuous years, she and Olivier divorced in 1960, and her mental illness often transformed her intelligent and sweet nature, making professional and personal relationships problematic at times. By the time she died, a ravaged 53 years old, Vivien Leigh had become one of the broken butterflies she had so often played on stage and screen.

Biography From TCM | Turner Classic Movies

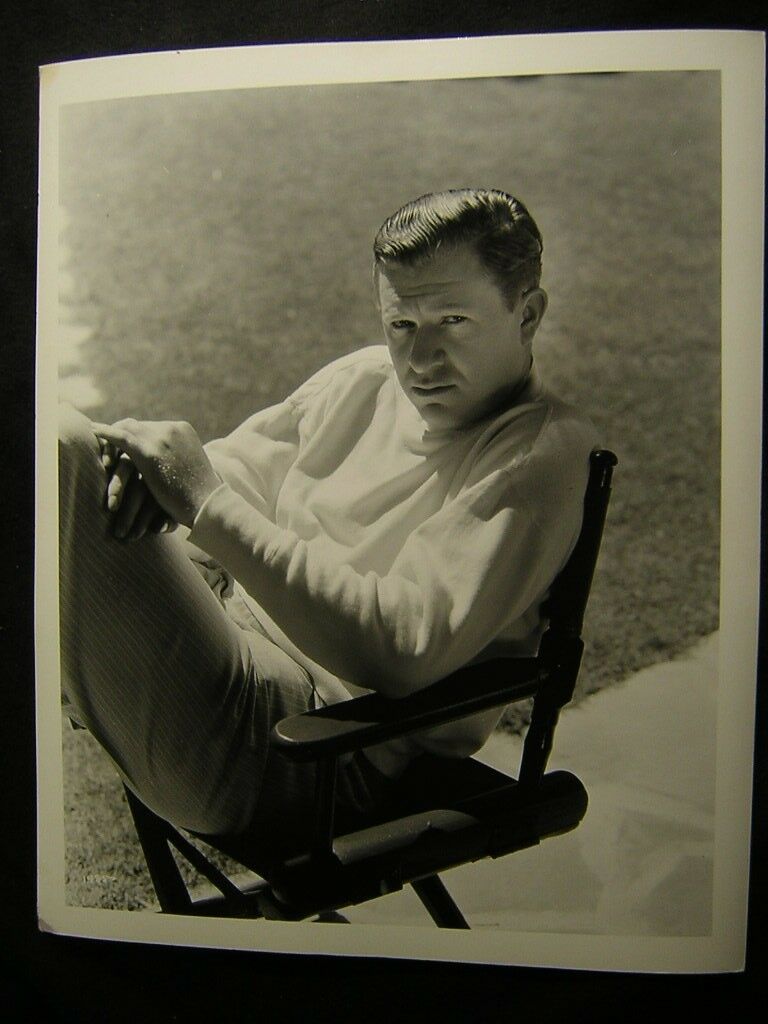

More about David O. Selznick:

A creative-minded executive who broke the mold and became one of the first truly successful independent producers, David O. Selznick rose to prominence during a time in American cinema where the early pioneers were being squeezed out by the emerging studio system and replaced by paint-by-the-numbers administrators who saw efficiency and profitability as their main objectives. Selznick had his start working his way up through MGM before becoming a vaunted producer under B.P. Schulberg's Paramount Pictures. He moved on to executive positions at RKO Pictures where he produced a number of films featuring strong female leads like "A Bill of Divorcement" (1932), "What Price Hollywood?" (1932) and "Little Women" (1933), while also steering the groundbreaking "King Kong" (1933) through production. Back at MGM, he produced quality adaptations of "David Copperfield" (1935) and "Anna Karenina" (1935) before branching out on his own as an independent producer with Selznick International Pictures. Releasing through United Artists, Selznick produced a number of critically successful films while winning back-to-back Best Picture Oscars for "Gone with the Wind" (1939) and "Rebecca" (1940). The former became one of the highest-grossing movies of all time on its way to winning 10 Academy Awards and being recognized as one of the finest movies ever made. After producing Alfred Hitchcock's mesmerizing thriller "Spellbound" (1945), Selznick was forced to liquidate his company before winding down his producing career with just a handful more films. Something of a maverick during his day, Selznick revolutionized the business end of filmmaking by managing to independently make quality motion pictures now considered exemplars of the Golden Age of the studio system.

Born on May 10, 1902 in Pittsburgh, PA, Selznick was raised by his father, Lewis Selznick, a silent movie producer who saw early success on the East Coast, only to suffer bankruptcy after setting up shop in 1920s Hollywood, and his mother, Florence. Following his attendance at Columbia University, Selznick began an apprenticeship in publicity and as a story analyst with his father until the elder went bankrupt in 1923. Three years later, the young Selznick joined the newly born MGM Studios as a script reader, and shortly rose to the head of the scenario department and finally production supervisor. But after a disagreement with producer Irving Thalberg, who preferred another supervisor on "White Shadows in the South Seas" (1928), Selznick was fired. His dismissal occurred during the advent of sound films, when the studios were consolidating power and seeking economic ways of adapting the new technology. Producers like Selznick were in great demand and B.P. Schulberg of Paramount Pictures hired him in 1927 to supervise the story department and writing staff. Before long, Selznick rose through the ranks to become an associate producer and later temporary production chief, while his brother, Myron Selznick, became one of the most powerful agents of his day until his death in 1944.

But Selznick chafed at Paramount's strict regimentation and when asked to take a heavy salary cut at the onset of the Great Depression in 1931, he resigned. Selznick found a new home at RKO Pictures, where he instituted a unit production scheme in which he oversaw the studio's top productions while delegating supervising duties for more routine features to a staff of seven assistant producers. At RKO, Selznick's predilection for glossily produced stories about self-sufficient females was first displayed in films like "A Bill of Divorcement" (1932), featuring Katharine Hepburn in her film debut, "What Price Hollywood?" (1932), with Constance Bennett, and "Little Women" (1933), which also starred Hepburn. He was also a producer on the iconic "King Kong" (1933), which broke new ground in special effects while becoming a major box office success. When MGM's Thalberg became seriously ill, Louis B. Mayer sought Selznick as a unit producer, an offer that was readily accepted. Now back at MGM, Selznick once again promoted strong production values and storylines, which usually meant an adaptation of a classic novel or popular play.

Following "Dancing Lady" (1933) and "Manhattan Melodrama" (1934), Selznick shepherded adaptations of some of literature's most popular works, including Charles Dickens' "David Copperfield" (1935) by George Cukor and "A Tale of Two Cities" (1935) from Jack Conway, as well as one of the most famous film productions of Leo Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina" (1935), starring Greta Garbo in the titular role. Selznick left MGM in 1936 to form his own independent company, Selznick International Pictures, and distributed movies through United Artists. His intention was to produce only a few prestige films each year, allowing him to meticulously follow the progress of every project, from selecting the properties to overseeing the shooting and supervising the editing and retakes, in order to achieve a degree of perfection unattainable in a studio environment. Without studio front office restrictions, however, Selznick's nitpicking ways went unchecked and the films emerged at a sluggish pace. When they were released, however, they were not merely films - they were major events. "The Garden of Allah" (1936), starring Marlene Dietrich, and "Little Lord Fauntleroy" (1936) were among the first pictures released by his new company, while Selznick's first major success came with "A Star is Born" (1937), which earned seven Academy Award nominations, becoming the first color film to receive a Best Picture nod.

Selznick soon followed with such critical and popular successes as the Carole Lombard screwball comedy "Nothing Sacred" (1937), "The Prisoner of Zenda" (1937) and Ingrid Bergman's American film debut "Intermezzo" (1939), before achieving his ultimate triumph with "Gone With the Wind" (1939), one of the most financially successful films ever made and winner of 10 Academy Awards. After paying a then-whopping ,000 for the rights to Margaret Mitchell's romantic bestseller, Selznick beat out the likes of Jack Warner as well as his old compatriots at RKO and MGM. Once he owned the rights, Selznick went through a number of potential actresses to play Scarlett O'Hara, eventually settling on little-known British starlet Vivien Leigh after filming had begun. Meanwhile, he was highly covetous of Clark Gable playing Rhett Butler and accepted a financially restrictive deal to loan the actor from MGM. But nearing production, Selznick fired longtime collaborator, director George Cukor, after objections raised by Gable and brought in Victor Fleming, who allegedly directed "Wind" and "The Wizard of Oz" (1939) concurrently. An epic romance set against the atrocities of the Civil War, "Gone with the Wind" followed the mercurial Scarlett O'Hara (Leigh), who falls for the scoundrel Rhett Butler (Gable) at the onset of the war. After suffer the indignity of hunger and the ravages of the burning of Atlanta, Scarlett eventually agrees to marry Rhett, who hopes she will eventually reciprocate his love instead of pining for family friend Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard), only to suffer a tragedy that drives the pair apart for good. Ending with Rhett's line "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn," arguably the most famous in cinema history, "Gone with the Wind" became one of the most iconic films of the era while boasting the distinction of featuring the first African-American actress, Hattie McDaniel, to win an Academy Award.

Because of the success of "Gone with the Wind," Selznick's production company became the top money-making studio in Hollywood in 1940. Meanwhile, he brought British director Alfred Hitchcock to Hollywood to direct his first American film, "Rebecca" (1940), a psychological thriller about a naïve young woman (Joan Fontaine) newly married to an aristocratic widower (Laurence Olivier) who moves into his country estate, only to slowly discover that his first wife died under mysterious circumstances. Not only was "Rebecca" one of Hitchcock's most enduring films, it also was a big hit for Selznick that also won him his second Best Picture Academy Award. Ironically, it was the financial success of his films that actually led to the dissolving of Selznick International Pictures. Because he had no major studio set-up in which to reinvest the profits he made, Selznick was faced with a substantial tax burden that led to a deal with the Internal Revenue Service to liquidate the company over a span of three years. One of the final pictures he released under the banner was Hitchcock's superb thriller, "Spellbound" (1945), starring Ingrid Bergman as a psychoanalyst who falls in love with her boss (Gregory Peck), an amnesiac who may or may not be a killer.

After releasing Hitchcock's "The Paradine Case" (1947) and dissolving his production company, Selznick immediately formed David Selznick Productions and set about trying to match the success of his own benchmark, "Gone with The Wind." The closest he came was "Duel in the Sun" (1946), an overblown and overtly sexualized Western dubbed "Lust in the Dust" that starred Gregory Peck and Selznick's future second wife, Jennifer Jones. Selznick and Jones had begun an illicit affair while both were married - he to Irene Mayer, a theatrical producer and daughter to Louis B. Mayer, while Jones had wed Robert Walker, an actor who secured a contract with MGM thanks to Selznick's own efforts. Jones and Walker divorced in 1945, which left him in a severe state of depression that led to alcoholism, a stay in a mental health facility and eventually his death at 32 from an accidental overdose of barbiturates and alcohol. Meanwhile, Selznick divorced Mayer in 1948 and married Jones the following year, with whom he had one daughter, Mary, a victim of suicide at 21 years old. Neither apparently looked back at the wreckage left in their wake.

Meanwhile, Selznick produced fewer films after "Portrait of Jennie" (1948), a romantic drama about an impoverished painter (Joseph Cotten), who becomes attracted to an enigmatic young woman (Jones), only to slowly realize that she may be the ghost of a girl who died in a hurricane years ago. Though later considered to be a minor classic, "Portrait of Jennie" was not a success upon release. Selznick stepped away from producing films largely to support Jones' career while also realizing that the advent of television threatened the movie business. He did try his hand at television producing with the two-hour "Light's Diamond Jubilee" (1954), which aired on all four television networks. On the big screen, Selznick was one of the producers on the classic espionage thriller, "The Third Man" (1950), before returning to the more mawkish sentimentality of "Gone to Earth" (1952) and a remake of "A Farewell to Arms" (1957), starring Jones and Rock Hudson. The latter marked the last time the Selznick name graced a film. He went into retirement while Jones also wound down her own career. Following a number of heart attacks, Selznick died on June 22, 1965 in Los Angeles. He was 63. A giant that loomed over the industry both during and after his death, Selznick played a significant role in creating the mystique and glamour of classic Hollywood. Moreover, he showed that it was possible, however briefly, to work outside the studio system and still produce films of technical polish and timeless appeal.

Biography From TCM | Turner Classic Movies