-40%

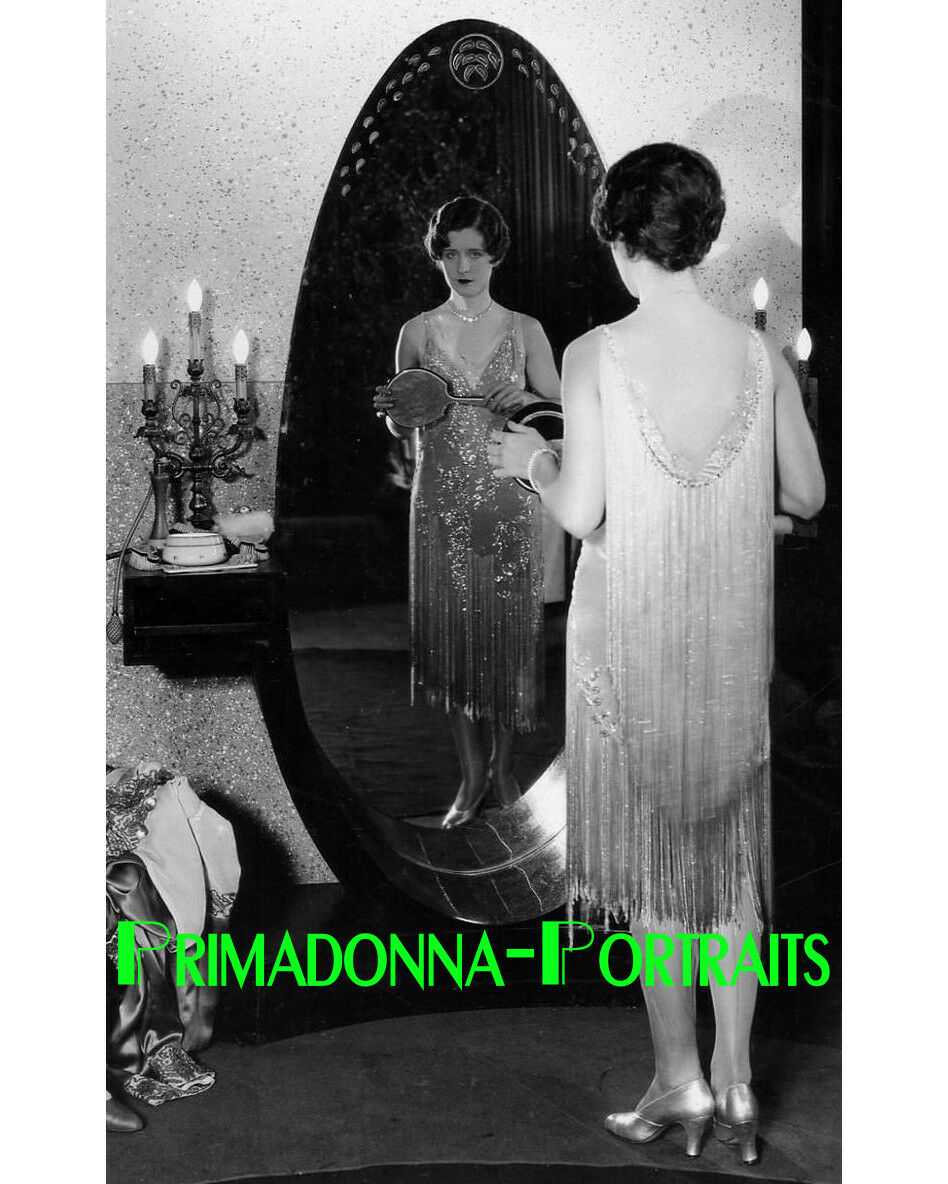

Silent Film Vamp Louise Glaum Beautiful 1910s Apeda Glamour Photograph Original

$ 2.61

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

ITEM: This is a 1910s vintage and original photograph of dark-haired, melodramatic actress Louise Glaum. Photographed by Apeda Studio for the N.Y. Motion Picture Corp., Glaum is mysterious and beautiful in this bohemian portrait. Called "The Spider Woman" or "The Tiger Woman," she was one of the silent screen's most infamous and exotic vamps. At one time a serious rival to Theda Bara, a critic dubbed Louise the "best actress of all the screen vamps". As the vamp fad began to outstay its welcome, her popularity also declined.Photograph measures just shy of 8" x 10" on a matte double weight paper stock with handwritten notations on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Louise Glaum:

Louise Glaum (September 4, 1888 – November 25, 1970) was an American actress. Known for her roles as a vamp in silent era motion picture dramas, she was credited with giving one of the best characterizations of a vamp in her early career.

Glaum began her acting career on the stage in Los Angeles, her hometown, in 1907. After a few years, she went on the road with a touring company and performed as an ingenue in the play Why Girls Leave Home. She stayed on in Chicago, where she appeared in a number of productions. After returning to Los Angeles in 1911 because of the death of her younger sister, Glaum found acting work at a movie studio. She appeared in over 110 movies from 1912 to 1925, her debut being in When the Heart Calls.

After starring in Greater Than Love (1921), she retired from the screen and moved to New York. In 1925, she sued for money owed her for movie work amounting to 3,000. The suit was ultimately dismissed by the court due to technicalities. Glaum made a final movie appearance in 1925. Under contract with Associated Exhibitors, she starred as the conniving other woman opposite Lionel Barrymore in a drama directed by Henri Diamant-Berger titled Fifty-Fifty.

For over three years, Glaum headlined on the vaudeville circuit in dramatic playlets. She presented a play in which she starred, Trial Marriage, in Los Angeles in 1928. Continuing to act on the stage, she opened and appeared in her own theatre in Los Angeles in the mid-1930s and became a drama instructor. Glaum was active in music clubs over the following decades. She served as president of the Matinee Musical Club for many years and was also state president of the California Federation of Music Clubs.

Glaum was born near Baltimore, Maryland, the third of four daughters of John W. Glaum (July 9, 1856 – July 7, 1934) and Lena Katherine Kuhn (December 30, 1863 – July 1, 1946). Her sisters were Hattie Helen "Phyllis" Glaum (September 7, 1884 – February 4, 1941), Lena K. Glaum (December 22, 1887 – January 15, 1971), and Margaret Olive Glaum (October 11, 1896 – June 18, 1911).

Her father was born as Johannes Wilhelm Glaum in Germany, emigrated with his family to the U.S. in 1869, and lived in Indiana, then Prince George's County, Maryland, while her mother was born in New York City to German-born parents. John and Lena Glaum and family moved to Southern California in the late 1890s, and lived in Pasadena for several years before moving into Los Angeles. Louise attended Berendo School on South Berendo Street in Pico Heights.

Glaum began her acting career in stock stage productions. She was in the cast of Crucifixus, a Passion play, which opened on November 12, 1907, at the Gamut Auditorium, 1044 South Hope Street, in Los Angeles, before a good-sized audience. In early June 1908, she appeared in the Owen Davis play How Baxter Butted In, a melodramatic comedy, at the Los Angeles Theatre on Spring Street. The cast included Lulu Warrenton and a number of others. Glaum then toured as an ingenue with a road show in Why Girls Leave Home. She earned a week and furnished her own gowns, which she made herself. After reaching Chicago, she played ingenues in the Imperial Stock Company there for a year and a half, appearing in The Lion and the Mouse and The Squaw Man, among other plays. While performing in a summer stock engagement in Toledo, she created the ingenue role in Officer 666. Its playwright, Augustin MacHugh, who was also her theatre director in Toledo, tried it out there before Broadway ever saw the successful farce.

Upon the death of her younger sister, Margaret, in June 1911, Glaum resigned and returned home to Los Angeles. On July 29, the Los Angeles Times read, "Louise Glaum, ingenue, who made her professional start here a few years ago, is at home on a short visit. Of late she has been playing in Chicago."

Her mother wanted her to remain in Los Angeles, but the desire to return to the stage possessed her. She compromised, however; while acting as the ingenue in a local theatre company, she began making the rounds of the movie studios.

Glaum made her movie debut playing the ingenue role as Mary Gordon, the rancher's daughter, in the Al Christie directed short western/comedy When the Heart Calls (1912) at Nestor Studios, the first studio actually located in Hollywood. She acted in straight comedy, never doing slapstick, from the start, and played leads exclusively. She starred in the title role of the Broncho Motion Picture Company's two-reel drama The Quakeress (1913) opposite Charles Ray and the ill-fated William Desmond Taylor. The year Glaum arrived, Nestor was merged with the Universal Film Company. A large number of episodes in the Universal Ike series of one-reel comedies are among her body of work in 1914.

Signing with Thomas Ince, her first role as a vamp, and first starring role in the new five-reel features, was as Mademoiselle Poppea in The Toast of Death (1915) opposite Harry Keenan and Herschel Mayall. It was directed by Thomas Ince at his Inceville Studio in Topanga Canyon. That same year, she appeared in the role as cabaret star Kitty Molloy in The Iron Strain, the first American film adaptation of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew, a modern version in which she starred opposite Dustin Farnum, Enid Markey, and Charles K. French.

Glaum played Milady de Winter in The Three Musketeers (1916). She appeared in six westerns opposite William S. Hart, including her roles as Dolly in Hell's Hinges (1916), Trixie in The Aryan (1916) and Poppy in The Return of Draw Egan (1916). She played Leila Aradella in The Wolf Woman (1916); and Marie Chaumontel in the war drama Somewhere in France (1916) opposite Howard C. Hickman.

On February 27, 1915, she and director Harry J. Edwards (October 11, 1887 – May 26, 1952) were married. They were divorced on March 17, 1919.

Glaum played the role as Lola Montrose in the drama A Strange Transgressor (1917). Then, totally opposite to dramatic type, she starred in the title role as a gun slinging heroine, the female equivalent to Bill Hart, in the Triangle Company's western Golden Rule Kate (1917).

She played Mary Thorne in the drama The Goddess of Lost Lake (1918), which she also co-produced through her own production company, the Louise Glaum Organization. It is the story of a young woman who is a quarter Native American and decides to pretend she is a full-blooded Indian princess when she visits her father's rustic cabin after completing college in the East.

Glaum then began working with J. Parker Read Jr. Productions, which she later described as J. Parker Read, Jr.'s unit as a subsidiary producing company for Thomas Ince. She signed a four-year contract, with a salary starting at ,000 a week and increasing to ,000, and some of the features she starred in for that company were as Mignon in Sahara (1919), a big financial success that was written especially for the star by C. Gardner Sullivan, with the production supervised by Allan Dwan; and the dual roles as Princess Sonia and as her daughter, Sonia, in the crime/thriller The Lone Wolf's Daughter (1919).

She played the roles as Adrienne Renault in the provocatively titled Sex (1920), the story of a New York cabaret star who uses her sex appeal to end a marriage then leaves her lover for a wealthier prospect only to have her selfish way of life come back to haunt her; and the title role in The Leopard Woman (1920), a secret agent adventure set in Africa. She then played the role as Natalie Storm in a romance/drama titled Love (1920).

Glaum was maintaining her own household in Los Angeles, when the 1920 census was enumerated, with a married couple, housekeeper and caretaker, and a gardener. After starring in the role as Grace Merrill in the drama Greater Than Love (1921), directed by Fred Niblo, she retired from the screen and moved to New York.

On March 16, 1925, she filed suit in the Supreme Court of New York against producer J. Parker Read, Jr., for 3,000 and asked for an attachment against money owed him by various film distributors in New York City. The complaint stated she was starred in several pictures under Read's direction, and on December 23, 1921, he made a promissory note to her for the money, payable in four installments. Nothing was paid, however, and in the Fall of 1923, according to Glaum, he went to Paris without paying her. According to her attorney, Read's departure took the form of a flight and he had disguised himself as a stoker on a ship.

She then sued the estate of Thomas H. Ince, Read's partner, stating that Read was insolvent and asking for the 3,000 plus 0,000 for breach of contract. The Appellate Division, however, decided that she could not prosecute a suit in the state against the executors under the will of Ince on the grounds that the New York courts had no jurisdiction over the executors, who were appointed in California, in which state Ince was a resident at the time he died in November 1924. She then filed suit in California, but a copy of the contract was not attached. By the time that arrived, the time had elapsed in which she was legally entitled to make a claim against the Ince estate and the court dismissed the suit on technicalities.

She made one screen comeback. Signing a contract with Associated Exhibitors, she played the role as Nina Olmstead, the conniving other woman, in the Henri Diamant-Berger directed drama Fifty-Fifty (1925) opposite Hope Hampton and Lionel Barrymore.

Glaum stayed away from Los Angeles for over three years as she headlined on the big-time vaudeville circuit in the East. She did a tour of Loew's Theatres in two dramatic playlets. One of them was The Sins of Julia Boyd by Paul Gerard Smith. The other was The Web, which Glaum wrote herself. She was the only character in the one person show, putting over the argument of the piece chiefly by a telephone conversation.

On January 19, 1926, Glaum and movie theater owner Zachary M. Harris (January 22, 1878 – March 5, 1964) were married in New York City.

When she returned to Los Angeles, with her husband and business manager, Zack Harris, to visit her family and friends, they decided to stage the play Trial Marriage at the Egan Theatre, 1320 South Figueroa Street, with Glaum in the starring role. When asked by a reporter for the Times whether she would be doing any picture work, she said she had not thought of it, but acknowledged that she was interested in talking pictures.

On November 16, 1928, Glaum opened in Trial Marriage, the story of a woman who wants to test the suitability of her prospective mate and herself to each other without the benefit of wedlock before they make it permanent. Although she received good reviews, the play did not fare so well.

She and Harris lived at 2282 Cambridge Street in Los Angeles, in 1930. Glaum continued to act on the stage and also became a drama instructor, opening and appearing in her own theatre in Los Angeles in the mid-1930s.

On January 6, 1935, Glaum announced in the Los Angeles Times the opening of the Louise Glaum Little Theatre of Union Square, which was inside a remodeled and redecorated movie theater with a seating capacity of 400 located at 1122 West 24th Street near Hoover in the West Adams District. The stated purpose was to provide drama with enlivening moments by way of scheduled plays of moment and actual integrity. Several New York plays were considered, and the intention was to present original manuscripts with motion picture possibilities, as well as tried plays from around the world. Both professionals and students were to be cast in productions, as well as some of the featured players of the past." Classes for students wanting to join the Union Square Players, and "learn by practical experience," began on January 21.

The little theatre generated a great deal of interest among local playwrights inasmuch as Glaum had received some 15 plays by January 27. One of the most intriguing was Eulalia Andreas's A Friendly Divorce, which went into rehearsal with Johnstone White directing. Noted stars were lured to perform. In March 1935, Glaum and Betty Blythe, another star of the silent screen, starred in Angel Cake, which was written by Ansella Hunter, who had three plays staged by the Shuberts.

In May, the Union Square Players presented the comedy Ask Herbert, which was written by Katherine Kavanaugh and declared in the Los Angeles Times to be "a riot of laughs" and "a fast-paced farce of Broadway caliber." Among the cast that Glaum assembled was Herbert Vigran, who went to New York and made his debut on Broadway later that year.

In 1936, Glaum joined the Matinee Musical Club. A drama department was introduced as an innovation to the club and Glaum was appointed the director. Plans for three one-act plays to be presented in November at the club were discussed by the department members on August 7, at the department chairman's home in Beverly Hills. She presented three one-act plays for the club on November 17, 1937, in the Creative Arts Center at 4950 Franklin Avenue in Hollywood.

In late September 1939, Glaum took over a theatre at 11th Street and Broadway in Downtown Los Angeles, designating it the "Louise Glaum's Happy Hollow." Opening on Wednesday night, September 27, in the rural play Aaron Slick From Pumpkin Creek, which had a continuous run for three months in Long Beach, specialties were offered between the acts.

Another rural play with specialties was presented at the Happy Hollow Playhouse on January 11, 1940, for the Matinee Musical Club, which had a Gay Nineties party at the theatre.

In September 1952, Glaum reopened the Beaux Arts Theatre, at the corner of West 8th Street and Beacon Avenue in Westlake, as the Louise Glaum Playhouse, which was generally referred to as the Louise Glaum Beaux Arts Theatre. The initial attraction, which she produced, staged and directed, was a comedy farce titled O.K. By Me, which was written by Sheldon Sheppard. The play concluded a seven-week run on November 22.

Glaum was also a busy clubwoman over the last three decades of her life. She served as president of the Matinee Musical Club for many years and also as state president of the California Federation of Music Clubs.

Louise Glaum died at age 82 of pneumonia in Los Angeles. Her funeral service was held at 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, November 28, 1970, at Pierce Brothers Mortuary, 720 West Washington Boulevard. She is interred in Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery, along with her second husband, Zachary Harris, and others of her family. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her work in motion pictures at 6834 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood.

Biography From: Wikipedia

More about Apeda Studio:

Alexander W. Dreyfoos (1877-1952)

Apeda was a diversified corporate studio located in New York City and organized in 1906 by partners Alexander W. Dreyfoos and Henry Obstfield. From its organization it pursued two business strategies: shooting original portraiture and reproducing uncopyrighted images by other photographers of newsworthy scenes or celebrities under its own trade name. Dreyfoos was the head photographer and to him goes credit for developing sports portraiture beyond baseball and boxing imagery into a wide-ranging field analogous to theatrical portraiture in its treatment and promotion.

Apeda's primary advantage among the New York metropolitan studios was its possession of industrial photograph developers and postcard printers. Whenever a New York photographer took a shot that they could not reproduce and market themselves or took a photograph that could not be copyrighted because there was no contract between photographer and sitter (the situation of flashlight stills of Broadway plays for instance), Apeda would secure a print, eradicate whatever name or trademark appeared on the print and affixed their own Apeda signature.

In 1912 they began selling copies of White Studio's production stills for "The Chorus Lady," "A Gentleman of Leisure," Gentleman from Mississippi," and "Thais" under the Apeda name. Apeda won the ensuing law suit, White Studio v. Dreyfoos, in a landmark copyright case. The decision rested on the court's understanding of work for hire. If an actor hired White Studio to produce a portrait, there was nothing prohibiting him from going to Apeda to reproduce that image in hundreds of copies at lower cost than White would charge, since the actor himself holds the portrait copyright.

Like Underwood & Underwood, Apeda would buy up the entire production archive of photographers who had business difficulties or were moving to other parts of the country. Apeda, for instance, bought up the negatives of the Geisler-Andrews firm after the partners split. In the 1920s, Obstfeld surrendered management of the business to Harold Danziger, whose background was in theater management. Dreyfoos remained head photographer, lensing sittings himself, and overseeing a small staff of event photographers and college yearbook portraitists.

During the mid-1930s and 1940s, Apeda left off performing arts work, turning to advertising imagery, industrial photography, high school class portraiture, and Armed Services portraiture. In the later 20th century, it was reorganized as Apco Apeda and operated until the 1990s when its New York headquarters encountered difficulties with the Environmental Protection Agency for chemical pollution. David S. Shields/ALS

Specialty:

The several photographers who contracted for work with Apeda over the years were conversant in every contemporary portrait styles, often imitating signal features of high profile photographers of the day. If there was any discernible ability characteristic of the company's photography, it was the ability to portray the whole body of the subject. While whole body portraiture was normal in sports and dance photography, it grew infrequent in 1920s theatrical portraiture, whole body shots being associated with production stills. Apeda photographers bucked the trend, producing whole body non-production portraiture after it went out fashion in Manhattan.

Biography By: Dr. David S. Shields, McClintock Professor, University of South Carolina,

Photography & the American Stage | The Visual Culture of American Theater 1865-1965