-40%

Flapper Joan Crawford w/ Bob Pixie Cut Orig. 1928 Ruth Harriet Louise Photograph

$ 2.61

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

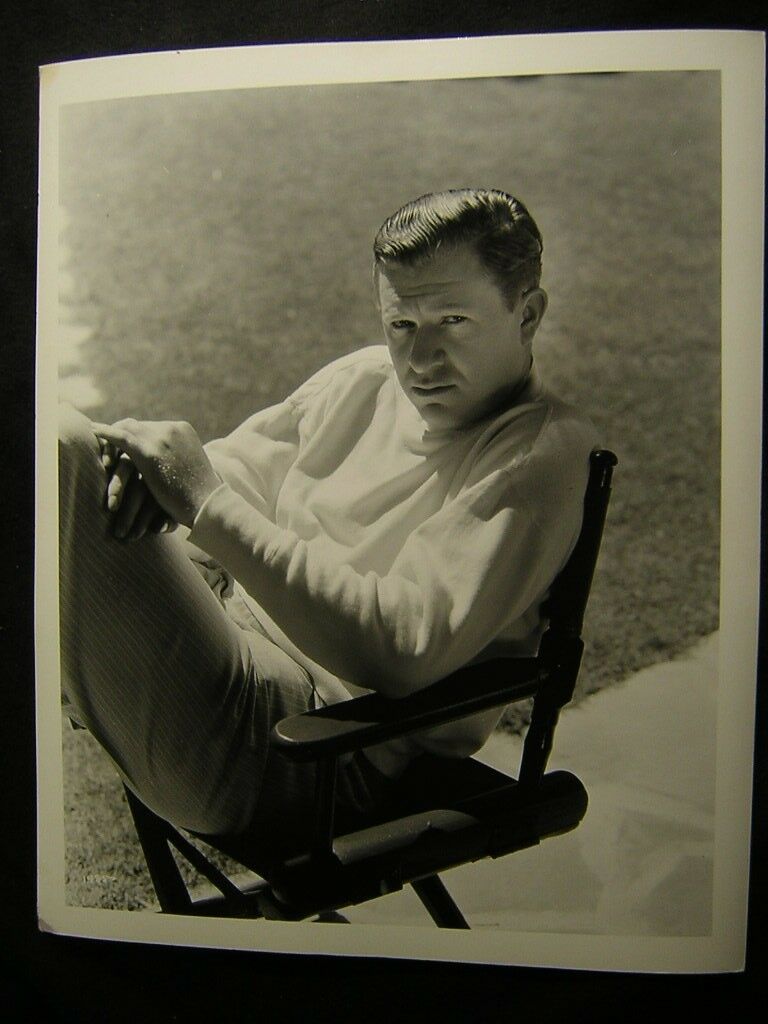

ITEM: This is a 1928 vintage and original Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer photograph featuring cinema icon Joan Crawford. Sporting a bob pixie cut in the flapper style, Crawford has been photographed in an alluring soft focus by Ruth Harriet Louise.The first, and at the time only, female photographer active in Hollywood, Louise ran MGM's portrait studio from 1925-1930 and photographed Crawford on several occasions over the years. Though not stamped, this is from a known sitting between Crawford and Louise.

Like the ambitious, upwardly mobile working women she became famous for portraying, Joan Crawford forged one of the longest-lasting and brightest-burning careers of Hollywood’s golden age through her fierce determination, dedication to her craft, and remarkable ability to continually reinvent herself. A commanding screen presence whose steely veneer and concentrated intensity could give way to tender vulnerability, Crawford endures as one of the most complex and endlessly fascinating icons of the studio era—a star in every sense of the word whose larger-than-life legend has only grown with time.

Photograph measures 8" x 10" on a glossy double weight paper stock with ink stamps and handwritten notations on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Joan Crawford:

Joan Crawford's extraordinary career encompassed over 45 years and some 80 films. After a tough, poor childhood, she was spotted in a chorus line by MGM and signed as an ingenue in 1925. Her portrayal of a good-hearted flapper in her 21st film, "Our Dancing Daughters" (1928), made her a star. Crawford maintained this status throughout the remainder of her career, but not without setbacks. She successfully made the transition to sound films, her Jazz Age image being replaced by young society matrons and sincere, upwardly mobile, sometimes gritty working girls (memorably in "Grand Hotel" 1932) and her mien adopting the carefully sculptured cheekbones, broad shoulders and full mouth audiences remember her for. Her MGM films of the 1930s, though lavish and stylish, were mostly routine and superficial. Despite mature and impressive performances in "The Women" (1939) and "A Woman's Face" (1941), both directed by George Cukor, Crawford continued to be given less-than-challenging roles by the studio.

In 1943 Crawford left MGM and her career took a decided upward turn after she signed with Warner Bros. the following year. In numerous Warner Bros. melodramas and "films noir," a new Crawford persona emerged: intelligent, often neurotic, powerful and sometimes ruthless, but also vulnerable and dependent. Memorable roles in "Mildred Pierce" (1945, for which she deservedly won an Oscar), "Humoresque" (1946) and "Possessed" (1947) restored and consolidated her popularity. In her nine "films noirs" for Warner Bros. and other studios, as well in most of her non-"noir" features (such as "Harriet Craig," 1950), Crawford gave expert and fully realized interpretations.

After this brief period of success, Crawford's career declined once again, and in 1952 her remarkable business acumen told her to leave Warners. She freelanced thereafter, notably for RKO in "Sudden Fear" (1952), a performance which earned Crawford her third Oscar nomination for Best Actress. She was also memorable as a female firebrand in Nicholas Ray's outrageously stylized Western, "Johnny Guitar" (1954). With the exception of "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" (1962), Crawford's performances of the 60s were mostly self-caricatures in second-rate horror films ("Berserk!" 1967, "Trog" 1970). Although these later features were poor vehicles for her talents, she was a resilient and consummate professional with an uncanny knowledge of the business of stardom who was fiercely loyal to her fans and who continued to impose the highest standards of performance upon herself. Crawford was married to actors Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and Franchot Tone and was portrayed as a cruel, violent and calculating mother by Faye Dunaway in the 1981 film, "Mommie Dearest," based on a scathing biography by her adopted daughter Christina.

Biography From: TCM | Turner Classic Movies

More about Ruth Harriet Louise:

Motion picture production jobs both on and off the set have mostly been held by men throughout history, and those for still photography are no different. Early stills men were mostly cameramen who also acted as photographers of scene stills, like Alvin Wyckoff for Selig Studios. D. W. Griffith hired James Woodbury to assist and take stills for “Intolerance,” and others started following suit. Studios created key books for each film, with photographs organized by scene number, and with each film assigned its own code. These images could be then be referenced and duplicated, to be sent out as publicity for the picture.

The studios soon realized that portraits of the stars could more easily sell films to consumers. These photographs were sent en masse to hundreds of magazines and newspapers, which required a never ending stream of material for publication. Portraits also were numbered in each studio’s own code system, and organized in key books as reference for approved shots of each star.

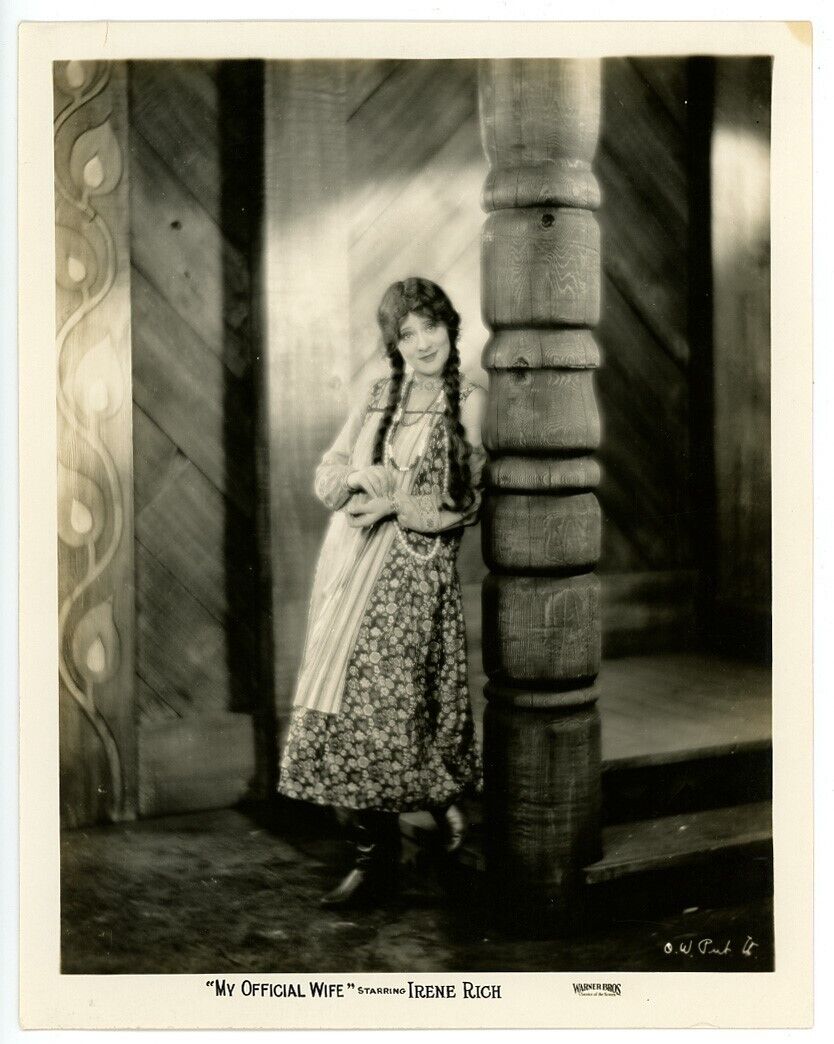

Most star portraits in the 1910s were taken by independent photographers like Albert Witzel, Hoover, Fred Hartsook, Melbourne Spurr, and the like. Mary Pickford hired her own photographer, K. O. Rahmn, and Mack Sennett hired the artistic James Abbe for some special shoots, along with such stills men as George Cannons and A. J. Kopec. Samuel Goldwyn hired Clarence Sinclair Bull in 1920, and Paramount hired Eugene Robert Richee in 1923. By the late 1920s, each studio possessed its own in-house photography studio and staff photographers. Ruth Harriet Louise was the only woman employed by any of the film studios during their glory days, and she acted independently, not just as a figurehead.

Born in New York on Jan. 13, 1903, Ruth Goldstein grew up as the daughter of Rabbi Jacob Goldstein and his wife, Klara, in New Jersey, along with her brother Mark. She dreamed of becoming a painter, but after a portrait session with the renowned New York photographer Nickolas Muray, she enrolled in a photographic school and apprenticed. In 1922 she opened her own studio in Trenton, N.J., advertising in “The Banner,” “Won’t you visit my studio, and let me perpetuate your personality,” per Robert Dance and Bruce Robertson’s “Ruth Harriet Louise and Hollywood Glamour Photography.” She quickly gained clientele, and by 1923 changed her name professionally to Ruth Harriet Louise.

Her brother Mark had followed their cousin Carmel Myers to Hollywood in 1922, and by 1925 he was writing and directing films. He had also professionally changed his name to Mark Sandrich, and would later direct Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in “Top Hat” and “Carefree” among others. Louise traveled across country later that year to join him in Los Angeles. She opened a little studio at Hollywood and Vine, and by September her first photograph appeared in “Photoplay” magazine, that of Vilma Banky in “Dark Angel” for Samuel Goldwyn.

Myers also assisted Louise; she showed studio chief Louis B. Mayer some of her portraits, and not longer after, Louise was hired as MGM’s in-house studio photographer. She was all of 22. On her -a-week salary, she would schedule five to six sessions a day, six days a week, crafting an elegant and glamorous image to sell to movie fans. To help loosen up the stars and help them find the mood she wanted, Louise played records. Her aim was to capture their personality, bottle it, and sell it to an eager public. Louise employed mood lighting, a soft, almost pictorialist style, and glamour in her shooting, and in her words, “…creating a personality.” Using 8 x 10 negatives, she produced both 11 x 14 and 8 x 10 prints after careful retouching and reframing.

Virtually all of the MGM stars liked her and enjoyed her company. She loved to sit around and talk after shooting, as well as joking and laughing while working. Louise seemed to enjoy working with almost everyone. She called Lillian Gish one of her favorite sitters in “Everybody’s Weekly,” on Sept. 8, 1928. She mentioned that she found Greta Garbo “…one of the saddest girls I’ve ever seen.” Louise described Lon Chaney as incredibly expressive and astute as to the moods she suggested. She found him an enigma however, described John Gilbert as a boy, William Haines as a more sophisticated boy, and Lillian Gish as a strong, in control person.

She played music to set the mood for what she wanted. Louise stated that Haines looked best when cheery songs like “Hallelujah” and “Girl Friend” played.

On Aug. 27, 1927, she married Universal writer Leigh Jacobson. The youngest writer on staff, he wrote westerns and serials and supervised their editing. Jacobson wanted to be a director so much he quit in December 1927 when the studio refused to allow him to switch. Making a two-reel film for ,000, he changed his name to Leigh Jason, and then attempted to sell it by states’ rights. Studio Chief Carl Laemmle saw it and asked to see the director. Laemmle rehired him as a director, but didn’t use the film.

Things began changing in Hollywood in the late 1920s. Unions came in to give workers more rights, better working conditions, and better wages. Stills photographers unionized as Local 659 in August 1928, but Louise never joined. The studio was growing astronomically from a family-like atmosphere to a huge conglomerate, and personal relationships altered and changed. There was less time to gossip and relax. Norma Shearer scheduled a sitting with George Hurrell to make more sexy stills, and Louise’s power diminished. The stock market crash also created a more tense atmosphere.

“Variety” reported on Dec. 11, 1929, that Louise had resigned from MGM, to be replaced by George Hurrell. The article stated she would start her own studio. As is the history in Hollywood, most resignations are often firings. Louise would take portraits of Anna Sten for Goldwyn and work out of her home for awhile, but the work soon petered out. She gave birth in 1931 to her first child, Leigh Jr., and daughter Brenda was born a few years later. In 1938, Leigh Jr. died of leukemia.

On Oct. 12, 1940, Louise died at the age of 37, from complications of childbirth, and the baby also died. Both The Los Angeles Times and Variety obituaries called her Mrs. Ruth Jason and listed her residence as 311 S. Beverly Glen Blvd. “Variety” does note that her professional name was Ruth Harriet Louise, under which she was “…one of the top portrait photographers…” in late 1920s Hollywood.

In 1942, her brother Mark donated two bungalows in her memory at the Motion Picture Country House. Jason would continue to direct, as well as invent. He applied for patents, particularly for a smokeless ashtray for theaters, airplanes, and cars, which GM would buy the rights for. In the early 1950s, he married Mark Sandrich’s niece Jerry Lieberman.

Louise’s work was little recognized for decades, until Dance and Robertson helped resurrect her memory with their excellent biography and exhibits of her work around the country. There are several important women stills photographers in Hollywood, and many famous portrait artists like Annie Leibowitz and Linda McCartney, who owe parts of their success to Ruth Harriet Louise and her blazing trail at MGM.

Biography By: Mary Mallory:

Hollywood Heights – Ruth Harriet Louise